Wesleyan Pilgrimage transforms heart and soul

By Erik Alsgaard

UMConnection Staff

Which came first: John Wesley’s conversion experience (“I felt my heart strangely warmed…”), or that of his brother, Charles Wesley?*

Knowing the answer to this question was just one of the fun facts I learned during a 10-day Wesley Pilgrimage in England. Sponsored by the Board of Discipleship, the Board of Higher Education and Ministry, and the General Commission on Archives and History, the July trip was almost non-stop learning, bus rides, walking tours and incredible experiences.

And no rain.

Our leaders were magnificent. The Rev. Paul Chilcote, Professor of Theology at Asbury Theological Seminary, Florida Dunnam Campus, was a walking history book of the Wesleys. His puns and frequent references to the movie “Zoolander” were most(ly) welcome, but his keen insights into the life and times of Samuel, Susanna, John and Charles Wesley were spellbinding. The Rev. Steve Manskar, now pastor at Trinity UMC in Grand Rapids, brought the covenant discipleship aspect of the Wesley’s to the fore, reminding us that the genius of the Methodist Movement lay not only in its ability to hold in tension two opposing forces (social holiness AND personal piety, for example), but in how it built disciples of Jesus Christ that really did transform the world (i.e., Francis Asbury).

SALISBURY

We 38 pilgrims began our time together in Salisbury, staying at Sarum College directly across the street from the cathedral. This was my first time in Salisbury, and the cathedral was absolutely magnificent. Viewing an original copy of the Magna Carta on display there at the Chapter House was a highlight, as was simply walking through the building, soaking in the views of stained glass, vaulted ceilings, soaring arches, and ancient sarcophagi.

John Wesley spent considerable time in Salisbury, first visiting in Feb. 1738, mainly because his mother was staying there at the time. It was here that John came in June that same year to tell her about his conversion experience.

Wesley established the Methodist society in Salisbury in 1750, and by 1758, a building was erected for a chapel. We visited that church for a lecture by the church’s pastor, the Rev. David Hookins, and again on a Sunday morning worship experience where we were warmly welcomed.

That warm welcome stood in stark contrast to the scene just a few blocks from the church, where police had blocked off a whole city street. White tents and people in haz-mat suits walked about. This was one of the areas where two people unwittingly, it appears, were poisoned by a nerve agent apparently used by Russian hitmen in an attempt to silence a former spy and his daughter three months ago. They survived, but one person died as the result of the exposure when, according to reports, she found what appeared to be a perfume bottle and sprayed Novichok on herself June 30.

OXFORD

The First Rise of Methodism began at Oxford, where both John and Charles Wesley were students. While attending Christ Church College, Charles Wesley and others began a regimen of daily prayer, study, meetings and small group accountability. “The Holy Club” was born. John came to the group later and, in typical fashion, his younger brother, Charles, let him take it over. Because of the group’s regular, methodical practices – which I think can be traced back to their mother’s tutelage at home – the derogatory name “Methodists” was used to describe them. The name stuck.

We pilgrims were given a small task on our visit to Oxford: find a plaque in the floor of Christ Church Cathedral that mentions the Wesleys.

My first clue as to the location was the fact that both brothers were ordained here. So, I walked up to the front of the altar, looking like a penguin waddling over the stones. No luck.

Then I remembered that John Wesley infamously preached a sermon in this Cathedral, wherein he questioned not only if true Christianity could be found in Oxford, but in the whole of the Church of England. (Editor’s note: Wrong church; he did this in the Church of St. Mary the Virgin, nearby.) Armed with this (wrong) information, I headed to the pulpit, and voila! There it was. Right at the foot of the steps you’d have to climb to preach.

Christ Church was packed with tourists the day we visited. That’s not unusual, I was told, because several of the scenes from the Harry Potter movies were shot there, including using the Great Hall (computer enhanced) as the dining hall.

We also took note of the Oxford Castle Prison, where members of the Holy Club visited inmates on a regular basis. Many of the prisoners were in jail because they couldn’t pay their debts (Samuel Wesley, the father of John and Charles, once spent three months in debtors’ prison). Their visits were especially important because, in the 1720s and 30s, there was no system in place to care for the inmates. That is, they were totally reliant on family members, friends or church members for food, clothing and other items.

EPWORTH

Now here is a place truly off the beaten path. One of the distinguishing marks between a tourist and a pilgrim, in my mind, is the intentional seeking out of things/places/events that don’t matter to the vast majority of people. Epworth is such a place.

A small village even today, Epworth is where John and Charles Wesley were born. Their father, Samuel, served as Rector of St. Andrew’s Parish, appointed there by the queen after he had written a poem, “The Life of Christ,” and dedicated it to her. (He also wrote another poem on maggots, but that’s another story.) Their mother, Susanna, bore Samuel 19 children: nine died in infancy; a maid accidentally smothered another infant; and when she died, only eight of the children were alive.

Life at the rectory was hard for Susanna. Samuel was away much of the time, and she was left to care not only for the children – who had a strict schedule of daily life – but, often, the church, too. I was surprised to learn that, at one point, when Samuel was away in London, 200+ miles to the south, Susanna started teaching parishioners in the kitchen. That’s because the associate pastor Samuel had left in charge was proving to be ineffective.

Soon, more people were attending her “services” than were attending church on Sunday morning. The associate pastor wrote letters to Samuel, complaining. Samuel then wrote letters to his wife, demanding that she (as a woman) stop doing this. One of her letters ended with these words:

“If you do, after all, think fit to dissolve this assembly, do not tell me that you desire me to do it, for that will not satisfy my conscience; but send me your positive command, in such full and express terms as may absolve me from all guilt and punishment for neglecting this opportunity of doing good, when you and I shall appear before the great and awful tribunal of our Lord Jesus Christ.”

We visited the rectory, and I was thrilled to stand in the garret on the top floor of the house where the home’s ghost, Old Geoffrey, lived.

But the biggest thrill of the pilgrimage awaited: the holy ground of St. Andrew’s Parish. Here, we stood around the baptismal font that was used to baptize John and Charles. Here, we held the silver communion chalice used for communion not only by Samuel, but by John and Charles. Here, we worshipped using an order of prayer from the 1600s. Here, we saw Samuel’s grave, just outside the church. It’s this grave that John famously stood on and preached from in 1742 when he was denied the pulpit inside the church

BRISTOL

If Oxford was the First Rise of Methodism, the Second Rise happened in Bristol. This southwestern city in England was important in Wesley’s day as a port which, infamously, made itself rich through the selling and buying of human beings. John Wesley was invited to come to Bristol by George Whitefield, who had been preaching to the poor and outcast. In March 1739, Wesley arrived, and within days he writes in his journal, “I submitted to be more vile,” (April 2, 1739) and he began to preach in the open air.

As a seminarian, I was fascinated by this “open air” preaching. It wasn’t until this pilgrimage, however, that I understood how radical it truly was. In those days, in the Church of England, the conventional wisdom was that a person could only be saved “inside” the church. That is, they had to literally be in the building to hear the sermon and be saved. Wesley’s words “to be more vile,” in my opinion, means that he saw an opportunity to reach more and more people with the Gospel and said, “to heck with the conventional wisdom,” and began to preach.

The results speak for themselves.

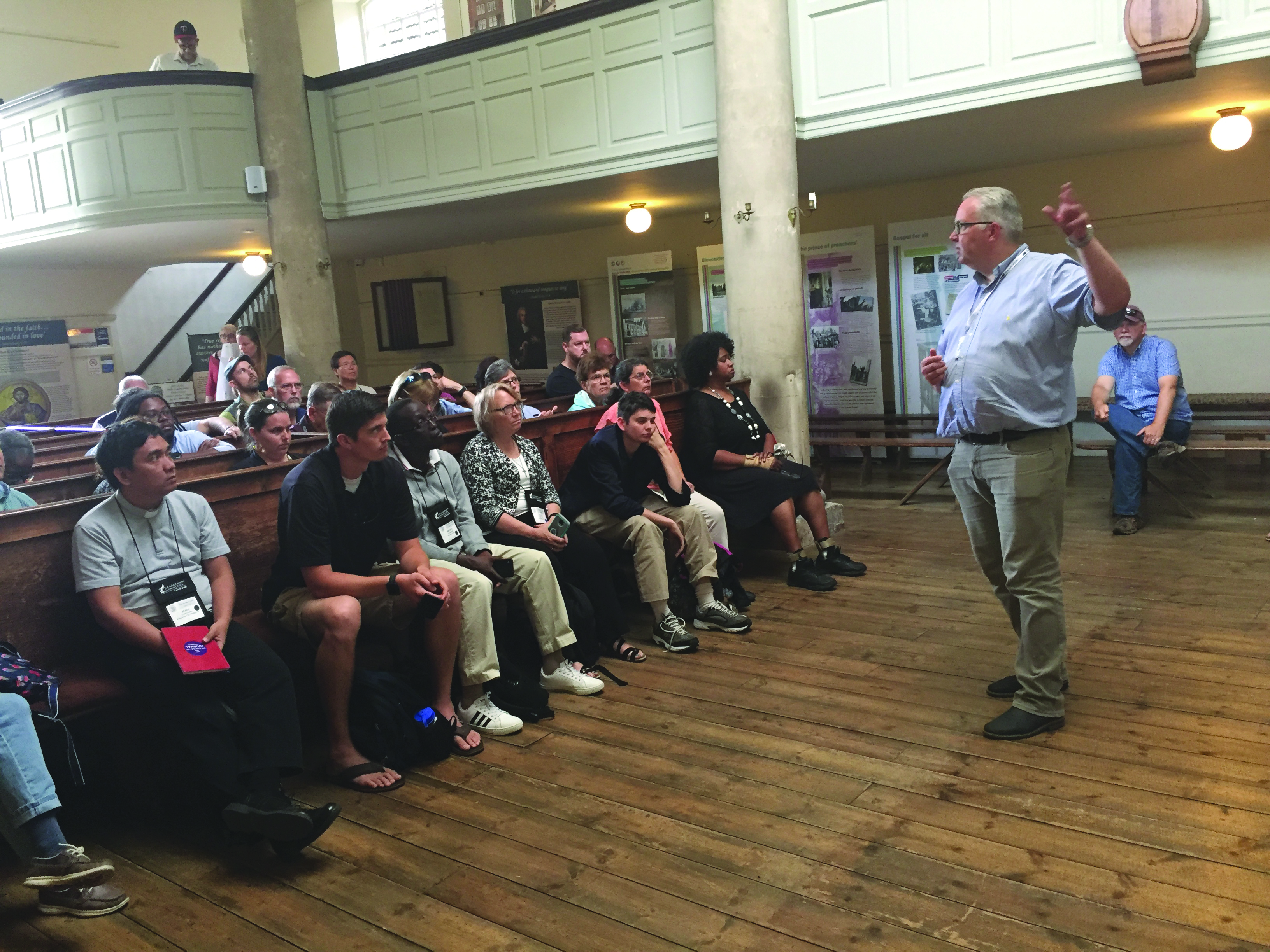

At Bristol, we pilgrims toured the New Room Chapel. Built in 1739, this is the oldest Methodist building in the world. The New Room was so-named because the two Methodist societies in Bristol at the time were running out of space in which to meet. Wesley built it to not only meet that need, but it was also an outpost for serving the community: food and clothing were given to the poor; visits were made to the nearby prison; a medical clinic was established; and more.

One feature pointed out by David Worthington, Director of the New Room, is that the ground floor of the building has no windows. The reason? In those days, Methodists were under attack by religious groups who considered them “enthusiasts,” or by people who simply didn’t understand what was going on.

As the New Room’s website describes it, “The early Methodists were frequently attacked by mobs. The lack of windows on the ground floor was a safety measure against such attack. The building was also designed so that it was difficult for any mob that broke in to reach the preacher quickly – witness the limited access upstairs (in the two-tiered pulpit).”

It was in Bristol that the resident Church of England bishop asked Wesley why he (Wesley) was infringing on his (the bishop’s) parish. You know – or should know – Wesley’s response. “Sir, I look upon the whole world as my parish.”

The New Room is also famous – at least in the United States – as the place where Francis Asbury attended his first Methodist conference (1771) and heard the call to go to the Colonies as a Methodist missionary. I was surprised to learn that Asbury is almost unheard of in British Methodist circles. My guess is because once he went to America, Asbury never returned, the only preacher sent by Wesley to stay. In fact, Bishop Asbury is buried in Baltimore.

LONDON

Our pilgrimage ended, appropriately, in London. I say “appropriately” because this is where John Wesley’s earthly pilgrimage ended, too, in 1791. He is buried behind the church he started there, now called Wesley Chapel. His mother, Susanna, is buried across the street in Bunhill (“Bone-hill”) Fields, along with about 100,000 other people (including Daniel DeFoe, John Bunyan – author of “Pilgrim’s Progress” – Isaac Watts, and William Shrubsole**).

Built in 1778 by John Wesley, the chapel that now bears his name was a replacement for the Foundery Chapel that began in 1739. Wesley’s townhouse, next door to the chapel, still stands, and it was here that he died.

Sitting in the pews at this chapel is always breathtaking to me. The pulpit here is one that John Wesley used many times. Margaret Thatcher was married here and later donated money to build the Communion railing. The baptismal font isn’t original – it was installed for the commemoration of the 100th anniversary of John Wesley’s death – but the Victorian bathrooms downstairs are, built in 1891 by Thomas Crapper.

It was in London that another highlight of the pilgrimage happened. On July 18, we pilgrims had the honor of sitting in the choir at St. Paul’s Cathedral for Evensong. My seat was at the far edge, second row, closest to the High Altar. Just sitting there gave me chills.

And so the pilgrimage came to an end. There is so much more I could write about – I have almost totally neglected the impact the Wesleys had on systematic disciple making that was stressed repeatedly during our pilgrimage – but I have run out of room and you, of patience in reading.

*As in more than a few other situations, Charles proceeded John. Charles’ happened on May21, 1738; John’s on May 24, 1738 (one wonders if the three days was significant).

** William Shrubsole wrote the hymn tune “Miles Lane,” to which is set one of my favorite hymns, “All Hail the Power of Jesus Name.” It’s not the tune you think you know…