Traveling the Circuit #11: Old Hay Bay Church

By Charles L. Harrell

On the shore of an inlet off Lake Ontario stands a stout but charming frame building, the oldest structure of the United Church of Canada. Known as the Old Hay Bay Church, it was actually founded as a Methodist chapel, the first of its kind in Upper Canada, part of what today we call the Province of Ontario.

Following the Treaty of Paris in September 1783, which ended the American Revolutionary War, British forces withdrew from New York City in November. That act brought to a close seven years during which New York was the center of Britain’s political and military effort to pacify its rebellious colonies, and a haven for those who did not embrace the cause of American independence. Many evacuated with the departing British troops as refugees that fall. Vilified as “Tories” and traitors in the United States, they were welcomed as “Loyalists” in the Canadas, which remained crown provinces. A wave of as many as 40,000 Loyalists would relocate northward, including the evacuees from New York who arrived in 1784 to carve a new home out of the hastily surveyed wilderness along the Bay of Quinte.

Among those pioneers was a significant number of adherents to the warm faith of the Wesleys: the Methodists. Underscoring their loyalty to “God, King, and country,” they organized several townships in the area, which they named for the children of King George III. The smallest and westernmost township was called Adolphustown; which sat straddling either side of an arm of water called Hay Bay.

At this point, the story of Hay Bay joins with that of a man named William, born in 1757 to the Losee family of Dutches County, New York. The Losees had been among the oldest pioneers from the days when New York had still been called New Netherland: William’s ancestor had emigrated from Utrecht, Holland, nearly a century before. When the move for independence came in 1776, the Losees were outspoken Tories. William, who lived something of a wildlife racing horses and rustling cattle, wanted to enlist with the King’s forces but was unable to, thanks to a damaged arm. Instead, he lent his support by foraging supplies for the redcoats, ultimately spending three years in a “rebel” (we would say “patriot”) prison after his capture. Crippled, his property seized, and with no apparent future in the newly-independent United States, William and evacuated from New York to Nova Scotia in 1783.

It was probably during his time there that Losee, having been exposed to Wesleyan preaching and the call to faith, repented and became a Methodist himself. Received “on trial” as a preacher in New York in 1789, he proved so effective on his circuit along the north shore of Lake Champlain in Lower Canada (Quebec), that he was ordained deacon and appointed as a missionary to Upper Canada by Bishop Francis Asbury in September of the same year, at Baltimore. (He would be received into full connection in absentia at the New York conference two years later.) In 1791, he arrived at Adolphustown and organized the first “class meeting” in Upper Canada to be established by a regular Methodist preacher. A second and a third such meetings were soon organized, and the Bay of Quinte Circuit, the first in what is now central Canada, was born. In time, Ontario would become the heartland of Methodism in Canada.

By 1792, the society at Adolphustown was ready to build a permanent meeting house, and built a chapel on the southern shore of Hay Bay. Measuring 30 by 36 feet with a gallery at the second-floor level, the frame structure was built in traditional New England fashion, “square with the sun at noon,” the entrance door facing due south. Funds for construction were raised through subscriptions, some quite generous for the time, by members of the community. Among the 22 original founders was Andrew Embury, son of Philip Embury, who had helped to establish John Street Church in New York City. The wording of the original subscription document survives. “We do agree,” the fellowship wrote,

to build said church under the direction of William Losee, Methodist preacher, our brother who has laboured with us this twelve months past, he following the directions of the Discipline of the Methodist Episcopal Church, or in his absence under the direction of any assistant Preacher belonging to the Methodist Episcopal Church in Great Britain or America, sent from there by proper authority (such as the Bishop) to labour among us. We do farther agree that NO other denomination or society of people shall have any privilege or liberty to preach or teach in the said Methodist church without the consent or leave of the assistant Methodist preacher then labouring with us.

The Hay Bay Church also served briefly as a courthouse for the township until a permanent building could be put up for that purpose. Ironically, however, no deed existed for the congregation’s ownership of the property until 1811, as it was not permitted for any denomination other than the Anglicans (and later, the Presbyterians) to own property until well into the 1800's. Even then, the fact that the Methodists in Canada were part of the American-based denomination caused them to be looked upon with suspicion by many within and outside of the government. Not until a separate Methodist Episcopal Church in Canada was organized in 1828, with the reluctant approval of the General Conference in the United States, did that problem begin to subside.

Meanwhile, in 1805, a field near the church was the scene of the first camp meeting in Canada, attended by as many as 250 people who had come mostly by boat, there being very few roads at this time. In 1811, Bishop Francis Asbury visited the area. Though a foot ailment prevented his coming to Hay Bay, his presence gave a boost to the Methodists in the region, and just in time: the following year’s outbreak of the War of 1812 forced American preachers living in Canada, who were now enemy aliens, to return south of the border. The Hay Bay Church was even used as a barracks for Canadian militia for a time, before peace was restored along the border.

A most formative and tragic episode in the history of the Hay Bay Church took place in 1819. On 29 August of that year, a boat bearing 18 young people coming across from the north shore to attend a quarterly conference at the church began to take on water, and sank, drowning 10 passengers in full view of family and friends onshore. All except one of the victims was buried across the road in the church’s cemetery, their markers standing silent witness to a terrible occasion of grief that is remembered in the community even to the present day.

A most formative and tragic episode in the history of the Hay Bay Church took place in 1819. On 29 August of that year, a boat bearing 18 young people coming across from the north shore to attend a quarterly conference at the church began to take on water, and sank, drowning 10 passengers in full view of family and friends onshore. All except one of the victims was buried across the road in the church’s cemetery, their markers standing silent witness to a terrible occasion of grief that is remembered in the community even to the present day.

As the church continued to grow, no doubt assisted by the union of the Canadian branches of the American denomination (Methodist Episcopal Church) and the British connection (Wesleyan Methodist Church) in 1832-1833, so did the need for additional space at Hay Bay. The congregation extended the church building to the north by fifteen feet, raised the roof line, and turned its design 90 degrees from an east-west to a north-south orientation, contributing to the building’s distinctive look. By 1858, however, a shift in the township’s population center, as well as the condition of the old building, resulted in a decision to relocate about three miles away to the site of the present Adolphustown United Church. The old church was emptied of its furnishings and appointments, and abandoned as a house of worship.

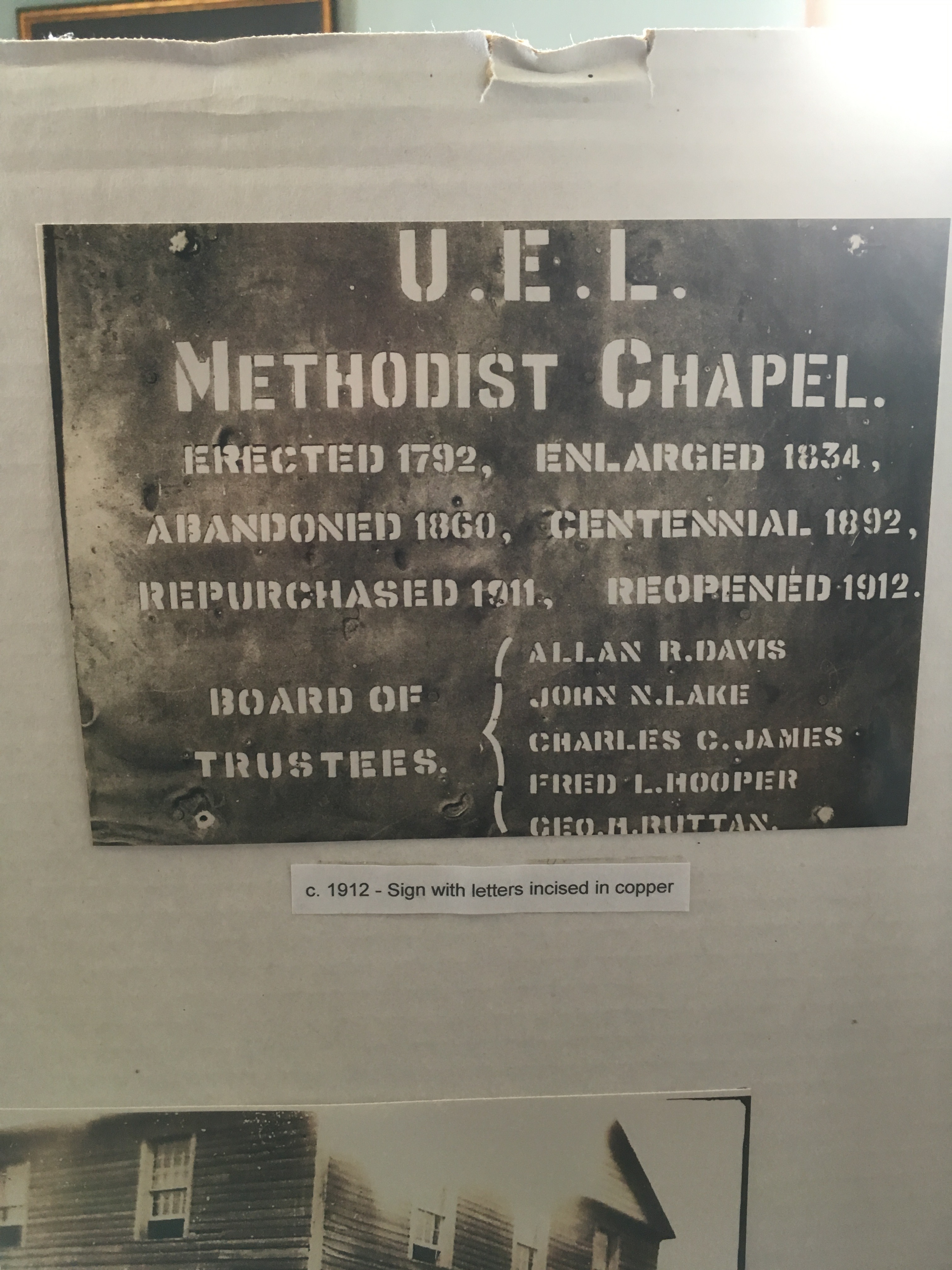

For about 50 years the former church building on the shore of Hay Bay was essentially a barn, storing grain and farm equipment. Thankfully, the church’s centenary in 1892 aroused interest in pursuing restoration of the site as a shrine of Canadian Methodism. Canada’s Methodist Church reacquired the property in 1910 and reopened it two years later amid great celebration. After the 1925 joining of the Methodist, Congregational, and Presbyterian churches to form the United Church of Canada, Old Hay Bay Church remained the oldest house of worship in the merged denomination. In 1992, it was designated a United Methodist Historic Site (no. 278) by the American denomination, and official recognition as a Canadian National Historic Site followed in 2000.

Today, this physical witness to early Canadian Methodism is maintained by the United Church of Canada and welcomes visitors during the spring and summer months (the church being unheated). Church groups are especially welcome but should make advance arrangements. Admission is free; but there is a restoration drive underway and donations are most welcome. Kathy Staples, the curator, graciously facilitated my visit and gave generously of her time and knowledge; she can be contacted by

. An annual service takes place at Old Hay Bay Church on the fourth Sunday in August. For general information, see the website. A small book and gift concession at the church focuses on Methodist and local history.

Today, this physical witness to early Canadian Methodism is maintained by the United Church of Canada and welcomes visitors during the spring and summer months (the church being unheated). Church groups are especially welcome but should make advance arrangements. Admission is free; but there is a restoration drive underway and donations are most welcome. Kathy Staples, the curator, graciously facilitated my visit and gave generously of her time and knowledge; she can be contacted by

. An annual service takes place at Old Hay Bay Church on the fourth Sunday in August. For general information, see the website. A small book and gift concession at the church focuses on Methodist and local history.

Old Hay Bay Church is located at 2368 S Shore Road, Napanee, Ontario K7R 3K7 Canada. It is almost midway by car between Toronto (3 hours) and Montréal (4 hours), about 32 km (20 miles) off the main east-west motorway (Ontario 401). Food and lodging can be obtained in the nearby town of Napanee. The Fox Motor Inn, in particular, offers friendly service and comfortable rooms at reasonable prices. Just 5 km (3 miles) from the church is a park marking the landing site of the first Loyalist settlers at Adolphustown in 1784. It is maintained by the United Empire Loyalists, an organization which is roughly the counterpart of the Daughters or Sons of the American Revolution in the United States (but honoring those who fought for the other side in the conflict). There is much Loyalist history throughout the area, providing a rare opportunity to see the struggle for American independence and its aftermath from the perspective of those who opposed it and were forced to leave their homes and flee north. For those who are interested, the Bay of Quinte area is also Ontario’s premier region for viticulture.

While you are in that part of Canada: about 90 minutes west by car, near the town of Bewdley in Hamilton township, lies the burial place of Joseph Scriven (1819-1886). Scriven wrote the words to the beloved hymn, “What a Friend We Have in Jesus.” Born in Ireland, Scriven emigrated to Canada following the drowning death of his fiancée. Upon learning that his mother was gravely ill back in Ireland, he wrote a poem that he titled “Pray without Ceasing” in order to console and encourage her:

What a Friend we have in Jesus, all our sins and griefs to bear;

What a privilege to carry everything to God in prayer.

O what peace we often forfeit, O what needless pain we bear,

All because we do not carry everything to God in prayer.

In Canada, he again fell in love with Eliza Catherine Roche, who died tragically from pneumonia in 1860. Scriven thereafter remained single for the rest of his life, and was known for his tutoring, preaching, and acts of charity that sprang from a deep faith. After his death under mysterious circumstances in nearby Rice Lake, he was buried at the tiny Pengelley Cemetery next to Miss Roche, and a monument erected in his memory by lovers of the hymn. It is a lovely and very peaceful location, with stately trees standing sentinel over the graves in a spot overlooking the lake.

In Canada, he again fell in love with Eliza Catherine Roche, who died tragically from pneumonia in 1860. Scriven thereafter remained single for the rest of his life, and was known for his tutoring, preaching, and acts of charity that sprang from a deep faith. After his death under mysterious circumstances in nearby Rice Lake, he was buried at the tiny Pengelley Cemetery next to Miss Roche, and a monument erected in his memory by lovers of the hymn. It is a lovely and very peaceful location, with stately trees standing sentinel over the graves in a spot overlooking the lake.

To visit the gravesite, take Ontario 401 to the exit for Northumberland County Highway 28, and follow it 16 km (10 miles) north toward Peterboro. The cemetery is located in a remote spot, at 69 Scriven Road in Bailieboro.

“Any visible thing that perpetuates the memory of a special providence is worth preserving,” wrote Rev. Richard Duke, one of the architects of the effort to restore and preserve Old Hay Bay Church in the 1890s.

We agree; and the Old Hay Bay Church and the Scriven gravesite alike attest to that God’s particular grace is with us in times of testing and difficulty, of personal pain and fresh starts in new places. They reward the pilgrim with fresh reminders of the Savior’s faithfulness in every age, and of the rich spiritual heritage of which we are heirs.