D.C. church repents for racism of its past

By Melissa Lauber

UMConnection Staff Kimberly Burge did not notice the inscription “Methodist Episcopal Church, South” carved above the entrance to the sanctuary when she first visited Mount Vernon Place UMC in Washington, D.C., last year. She didn’t know about the slaveholding bishops and pastors who built the church.

Kimberly Burge did not notice the inscription “Methodist Episcopal Church, South” carved above the entrance to the sanctuary when she first visited Mount Vernon Place UMC in Washington, D.C., last year. She didn’t know about the slaveholding bishops and pastors who built the church.

If she did, she said, she would not have attended. But she did visit, liked the people and began to participate in their book group on racial justice. Last Easter, she joined the church, and on Oct. 8, she led the congregation in a formal call to remembrance and repentance.

During the book group readings, which centered around the Black Lives Matter movement, Burge and others grappled with the history of their church, which was built by white

On Oct. 8, the congregation celebrated the 100th anniversary to the very day of the laying of the cornerstone. As part of the observance, Burge said, it was important to “name the sin of our racism and repent of our roots in white supremacy.”

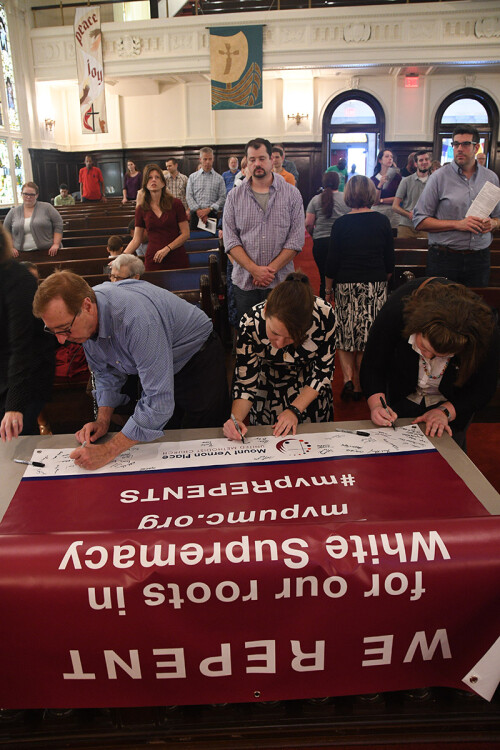

To make the naming personal, each worshipper at the celebration was invited to come forward, as they felt led, and sign their name to a banner claiming, “Mt. Vernon Repents,” which was then hung outside next to the 1917 cornerstone.

To make the naming personal, each worshipper at the celebration was invited to come forward, as they felt led, and sign their name to a banner claiming, “Mt. Vernon Repents,” which was then hung outside next to the 1917 cornerstone.

Before the congregation came forward, the Rev. Donna Claycomb Sokol, pastor at Mount Vernon Place, shared the church’s origin story.

Early Methodists, she said, in the 1780’s, condemned slavery as contrary to the laws of God, man, and nature and took a prophetic stance on “the sin of slavery.”

But as the South became more dependent on the production of cotton, tobacco

In 1832, the Rev. James Andrew was elected to the office of bishop. He did not have slaves when he

In 1846, the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, was formed. This branch of the church was “so entangled in the sins of bondage that every person elected to be a bishop in the Methodist Episcopal Church, South, between 1846 and the start of the Civil War was a slaveholder,” she said.

The church, said Claycomb Sokol, provided a theological framework to undergird the argument for slavery. “The gospel of Jesus Christ was replaced with the gospel of human bondage.”

A history of Mt. Vernon Place UMC says, “The Methodists were simply a part of the country and therefore a part of the division. All of the Southern states passed laws forbidding emancipation. The Southern Methodists took the position that ‘We must obey the law.’”

Mt. Vernon Place was built as the Representative Church of the ME Church, South, until the denomination reunited with its Northern counterpart and the Methodist Protestant Church in 1939.

The idea to build such a church for the denomination in the nation’s capital started in 1906. A massive $275,000 fund-raising appeal was held. One church in Texas told its members, “The Washington City Representative Church should be built at once, stately, majestic, magnificent and put right into the fight for the moral and religious welfare of our nation.”

“So here we are in this stunningly beautiful building,” said Claycomb Sokol. “Here we are in a building erected by people who believe it was okay to covet and take what didn’t belong to them; treasuring material wealth even over life itself.”

Claycomb Sokol was quick to point out that people in every era, including today, need to be honest about what they treasure and be willing to repent when that treasure draws them away from the will of God.

“None of us here can ever change what people treasured in the past,” she said. “But all of us can repent and turn around and seek to change, really change, what we treasure. We can turn around from what it is that has a grip on us and reorient our lives until our lives really are a sign of the fullness of God’s kingdom and reign on this earth, as it is in heaven.”

“None of us here can ever change what people treasured in the past,” she said. “But all of us can repent and turn around and seek to change, really change, what we treasure. We can turn around from what it is that has a grip on us and reorient our lives until our lives really are a sign of the fullness of God’s kingdom and reign on this earth, as it is in heaven.”

She encouraged everyone present to fill out their next step in addressing issues of race on response cards in the pews.

Since the laying of its cornerstone, Mt. Vernon Place has gone through several growth spurts and building booms. In 1960, it had 4,541 members. But in 2005, it had dwindled to 40.

In 2008, the congregation took a risk, selling two of its education and office buildings, which were attached to the sanctuary, to a developer, which razed them and built a 12-story retail and office space on the site. As part of the project, the sanctuary and church were restored; and Wesley Seminary rents part of the space for students to live in a missional community.

Today, the thriving, multi-generational, multi-cultural congregation has a meaningful outreach to the homeless in their community, including a robust shower ministry. “Our doors are open wider for all of God’s children to come inside,” Claycomb Sokol said.

The church’s study of racism and white privilege will continue, Burge said. “This is not about the past. Lives are at stake now. It’s about our own souls. … I need to be in a community that offers a different way to release shame and anger and bring the Kingdom of God a little bit closer.”

I had been in Washington on business and was on my way to the train station when I saw the sign outside the church. As someone originally from the south, who grew up in MI, I applaud finding a way to speak to the past while embracing the future. Well done.