Connectional Table continues anti-bias training

by Erik Alsgaard

More than 60 lay and clergy leaders in the Baltimore-Washington Conference, who make up the Connectional Table, participated in a virtual session Oct. 3, to continue their work of anti-bias training.

Noting that this work was “our ministry, not additional work,” Bishop LaTrelle Easterling opened the training by speaking about the “Ministry of Reconciliation,” found in 2 Corinthians 5:11-21.

“This is part of our baptism,” Bishop Easterling said. “We are covenanted to be in relationship with each other and with the world.”

The training, she said, was a continuation of the 2016 Northeastern Jurisdiction’s “Call to Action.” That pledge was made after the NEJ unanimously approved a resolution that called for the church to do more to fight discrimination to confront racism and to affirm that all lives matter in God's eyes.

That Call to Action, the bishop said, calls for training in all 10 of the annual conferences in the NEJ “to work against racism, white privilege and white supremacy, and to create more racial equity within each of our annual conferences.”

The leadership of each annual conference, Bishop Easterling said, are being called to “immerse ourselves in training that will give us cultural competencies to lead this work.”

Each annual conference in the NEJ – the 10 extend from Maine through West Virginia – has outlined steps they would take to further the work of the Call to Action. In the BWC, one of the first steps is for leaders across the board to take the Intercultural Development Inventory (IDI), a tool that “assesses intercultural competence — the capability to shift cultural perspective and appropriately adapt behavior to cultural differences and commonalities,” according to the company’s website.

Leading the training was Kristina Gonzalez, a United Methodist laywoman from Seattle, Washington. She said that the work of anti-bias training was to “slow down our reaction, to becoming attuned to our inculturation and that of others.”

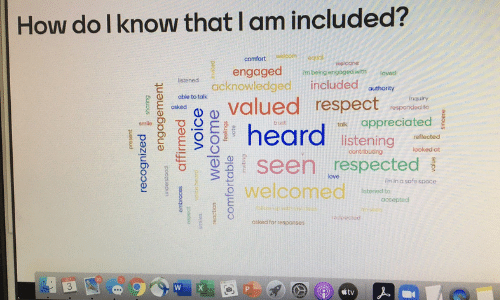

Gonzalez began by working on the topic of inclusion. She started there, she said, because of how inclusion is front and center in The United Methodist Church right now, especially around the issue of human sexuality and including LGBTQ+ people in the fullness of the denomination.

Gonzalez began by working on the topic of inclusion. She started there, she said, because of how inclusion is front and center in The United Methodist Church right now, especially around the issue of human sexuality and including LGBTQ+ people in the fullness of the denomination.

“We know what it feels like to be included,” she said. “And this is our work: to come to a place where that term actually has action associated with it that, no matter what our cultural background is, what our first language is…, (that) we have the opportunity of being a part of each other’s world.”

And, Gonzalez said, no matter the place from which a leader leads, there are always places of inclusion for others.

Learning about one’s own culture, she said, is the first step in growing one’s intercultural competency. That might sound like the wrong place to start, she said, but first knowing your own culture helps to allow a person to be confident in learning about others.

“Learning about my own culture is the gateway to understanding other cultures,” Gonzalez said. “Why is that? What we have a tendency to do if we’ve not done the deep work of uncovering what respect means to me in my community, then I have a tendency to judge others.”

Gonzalez spent time with the group exploring the difference between stereotypes and cultural generalizations.

“All women are emotional,” she said as an example, is a stereotype. Cultural generalization, however, is the tendency of a majority of people in a cultural group to hold certain values and beliefs, and to engage in certain patterns of behavior, she said. “They are research and researchable.”

The training was both theoretical and practical, as Gonzalez explored the many ways the information on cultural competency plays out in leadership.

“The Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity uses the theory that everyone enters this work from the same place,” Gonzalez said.

The model, she explained has six stages: denial, defense, minimization – which are all centered in one’s own ethnicity from which we make judgments – and acceptance, adaptation, and integration, meaning that “one understands their culture is one among many and that you do the work understanding culture in order to actually include,” she said.

“Your conference is really invested in this,” Gonzalez said. “The IDI is an inventory, not a test. It’s an empirical measure of the Developmental Model, and it’s a predictor of our behavior, validated across cross-culturally.”

Several leaders throughout the BWC have already taken the IDI, whose results are then plotted on the Model. All the members of the Connectional Table will take the inventory soon if they have not already.