Asbury UMC makes and tells historic stories

By Melissa Lauber

A mother, who is a doctor, wanted her young daughter to see the Black History Month art exhibit at Asbury UMC in Washington, D.C. But her daughter was immunocompromised, and attending an event where a lot of people might be present might have put her health at risk.

A mother, who is a doctor, wanted her young daughter to see the Black History Month art exhibit at Asbury UMC in Washington, D.C. But her daughter was immunocompromised, and attending an event where a lot of people might be present might have put her health at risk.

Carol Travis, a member at Asbury, immediately arranged to open the fellowship hall for a private tour. At Asbury, they are used to opening the doors wide to meet the physical and spiritual needs of all the people they encounter.

The church was established in 1836, built by slaves and freemasons. In 1864, during the Civil War, members built a stone church on the same site. The first Colored regiment to participate in the Civil War met in the church basement.

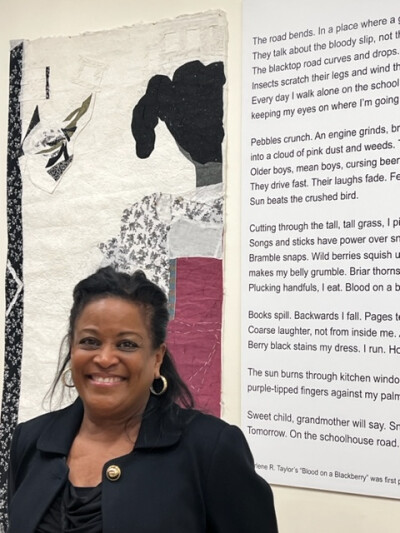

It was fitting that a mother and daughter sought out the art exhibit now on display. “Memories of a Dusty Road,” by Darlene Taylor, started with a photograph of Taylor’s ancestors, taken generations ago in Virginia. The baby being held in the photo is her grandmother’s sister.

These “porch-talking, story-teller women,” captured Taylor’s imagination. She found herself wondering what they were thinking, what stirred their hearts, what they confessed, and what they concealed. She wanted to stand with them, and know what they witnessed, what they remembered.

While working at the Columbus Museum of Art in Ohio as a writer-in-residence, she lived in the home of artist Aminah Robinson. While there, Taylor was in an automobile accident. During her convalescence, found herself making large collages out of rough mulberry paper, textiles, vintage lace and found objects, including some of her mother’s tablecloths.

The images illustrated her poem, “Blood on a Blackberry,” about a childhood trauma that unfolded on a dusty, dirt road.

It also drew upon her mother’s blackberry cobbler recipe and the heirloom narrative that ended up transcending mere ingredients.

Drawing on memory and history, Taylor, who worked in the corporate world and now teaches creative writing at Howard University in Washington, D.C., began to cut and glue and stitch together pieces that she wove into the voices of her grandmothers’ teachings.

Projecting the photo that originated her work onto a screen at Asbury, she explained “I wanted to touch those gazes. I don’t want them forgotten. Their witness, their whispers, their learning are stories I inherited.” History wanted to forget them, Taylor said. She placed them in the center and invited the world to journey along the dusty road with them.

Taylor’s artist talk, given on Feb. 10, is available on Asbury’s YouTube channel.

It dovetails with the church’s ongoing project of recording its members’ memories. Making and telling stories is an important part of Asbury’s ministry of loving, serving and transforming lives.

Creating this exhibit, helped Taylor discover the storyteller artist within her. She is now beginning to imagine new stories and history mapping that she wants to explore, including writing and illustrating the lost history of some Maryland women.

Re-reading “Blood on the Blackberry,” prompted her to ask, “what happens the next day?” She looks forward to discovering “what comes next.” For Taylor, the past is telling her future’s story.